A geostationary orbit (GEO) is a type of geosynchronous orbit where satellites remain fixed over the same spot on Earth’s equator. This section introduces the basic concept and its significance in modern technology.

Table of Contents

- Introduction

- Historical Development

- Technical Specifications

- Achieving Geostationary Orbit

- Applications

- Advantages

- Challenges and Limitations

- Future Prospects

- Conclusion

Introduction

Geostationary orbit, or GEO, is a unique equatorial orbit where satellites maintain a constant position relative to a point on Earth’s surface, matching the planet’s rotational period. This orbit lies 35,786 kilometers above sea level, where satellites complete one orbit in exactly 23 hours, 56 minutes, and 4 seconds—the time it takes for Earth to rotate once relative to the stars (sidereal day). This strategic positioning has profound implications for telecommunications, weather monitoring, navigation, and national security, making geostationary orbits a critical asset in the global satellite infrastructure.

Historical Context

The conceptual foundation of geostationary orbit was laid by Herman Potočnik in the 1920s, with a more detailed exposition by Arthur C. Clarke in his 1945 paper, “Extra-Terrestrial Relays – Can Rocket Stations Give Worldwide Radio Coverage?” Clarke’s vision of using geostationary satellites for global communication was visionary, with his predictions –

Historical Development

The idea of geostationary orbits was first proposed in the 1920s by Herman Potočnik and later popularized by Arthur C. Clarke. Here, we trace the journey from theoretical conception to practical implementation, including the first successful satellite in such an orbit.

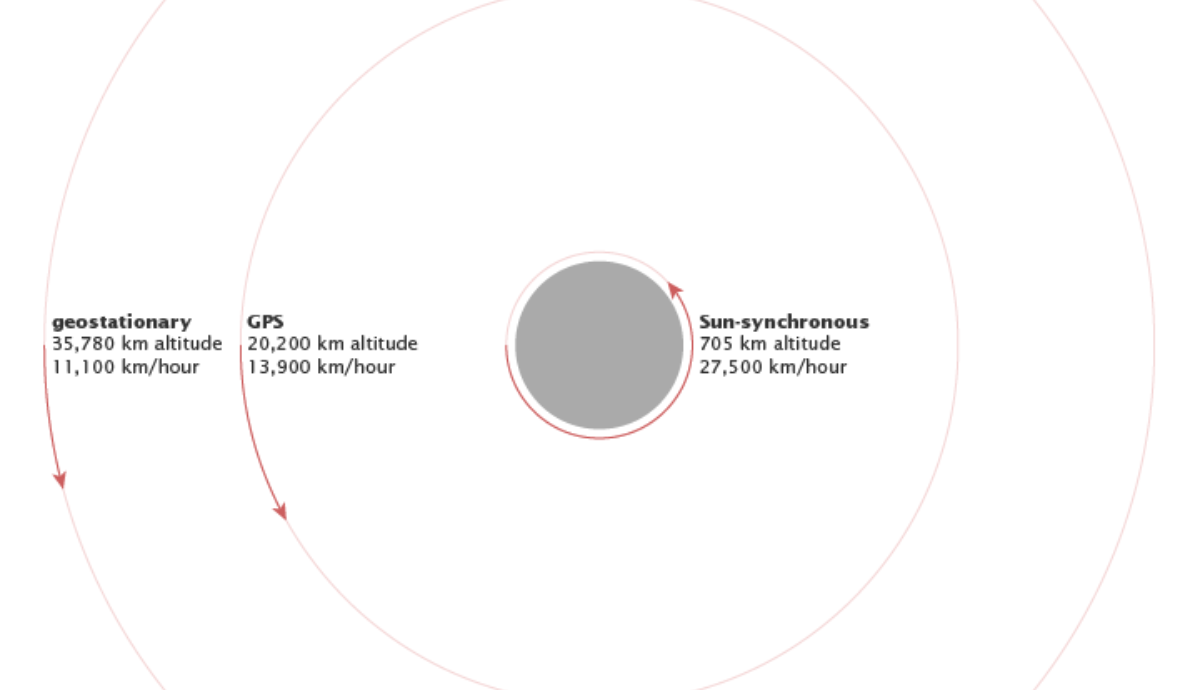

Technical Specifications

Altitude: Geostationary satellites orbit at 35,786 kilometers above the equator, allowing them to match Earth’s rotation and appear stationary in the sky.

Inclination: An inclination of zero degrees ensures the orbit is directly over the equator, keeping the satellite fixed relative to Earth’s surface.

Eccentricity: A near-zero eccentricity is crucial for a perfectly circular orbit, eliminating any variation in distance from Earth that would disrupt the geostationary positioning.

Orbital Period: The orbital period matches Earth’s sidereal day, approximately 23 hours, 56 minutes, and 4 seconds, synchronizing the satellite’s motion with Earth’s rotation for continuous coverage.

Achieving Geostationary Orbit

The launch vehicle propels the satellite into this GTO, often from launch sites like the Guiana Space Centre, which are near the equator to maximize the Earth’s rotational speed for an efficiency boost. Once in GTO, the satellite uses its onboard propulsion system to perform a critical maneuver known as the apogee kick motor (AKM) burn when it reaches the highest point of its elliptical path. This burn is designed to increase the satellite’s velocity, thereby circularizing the orbit by raising the perigee to match the apogee’s altitude.

Applications

Telecommunications: In telecommunications, geostationary orbit satellites are key players, providing extensive coverage for broadcasting television, radio, and multimedia content across continents. They enable internet service providers to extend broadband connectivity to remote areas and support international telephone and data networks, ensuring seamless global communication.

Weather Monitoring: For weather monitoring, geostationary satellites like those in the GOES series deliver continuous, real-time data essential for forecasting, tracking storms, and managing disasters, while also aiding in long-term climate observation.

Navigation: In navigation, geostationary satellites enhance regional systems like NavIC, offering improved accuracy for local applications, and support augmentation systems such as WAAS, which refine GPS signals for precise positioning in aviation, maritime, and land use.

Military and Intelligence: In the realms of military and intelligence, geostationary satellites provide persistent surveillance, secure communications for strategic operations, and early warning capabilities for missile detection, playing a crucial role in national defense and security

Advantages

Stable Coverage: GEO satellites offer unwavering focus on a single area, ensuring constant observation or communication for weather, defense, or telecom.

Simplified Ground Infrastructure: Antennas stay put with GEO satellites, reducing ground station complexity, costs, and maintenance, enhancing operational efficiency.

Global Coverage: Strategic placement of just three satellites in GEO allows near-global monitoring or broadcasting, covering vast regions simultaneously.

Challenges and Limitations

Orbital Slot Limitation: Limited slots in GEO mean intense competition, necessitating international coordination to prevent interference and ensure fair usage.

Signal Latency: The high altitude causes communication delays, impacting real-time applications like video calls or online gaming, making some uses less viable.

Maintenance: Satellites need periodic fuel use for station-keeping to counteract natural drifts, adding to operational costs and limiting satellite lifesp

Future Prospects

Technological advancements continue to shape the future of GEO. Innovations in propulsion, like electric thrusters, offer more sustainable operations. Orbit management strategies aim to mitigate space debris, ensuring these orbits remain viable for future use. New applications, including space-based solar power, are on the horizon, expanding the scope of geostationary orbits.

Conclusion

Geostationary orbits are a cornerstone of modern space technology, blending science, engineering, and global cooperation. Their importance spans across communication, safety, and security, with ongoing developments promising even greater utility. However, managing these orbits requires addressing challenges like slot scarcity, latency, and maintenance to ensure they remain a sustainable resource for the global community.